The Woodruff Gun: Researching the Woodruff Carriage

The Quest to Create an Authentic Replica Woodruff Carriage

by Randy Baehr

Around 1995, when I was researching the Filley gun, I had several telephone conversations with the foremost researcher of the Woodruff gun, Dr. John L. Margreiter , who, it turned out, lived only a few miles from me. In the last conversation I had with him, he mentioned that he had donated all his Woodruff research papers to the Missouri Historical Society, where I was later able to review them. He also mentioned that he was soon going to southwest Missouri to view a Woodruff carriage that had been “found in a barn”.1Author’s telephone conversation with John Margreiter, ca. 1995. At this point, and for two decades after, what kind of carriage Woodruff guns were mounted on was something that no one seemed to know, or if anyone did, no one was telling.

With the publisher’s permission, I had put the text of Margreiter’s Civil War Times article up on this website, along with additional information I had come across since it was published. In 2013, a website visitor, Shawn Clark of Independence, Missouri, contacted me with a link to the 1864 Helena photo on the website of the Trans-Mississippi Virtual Museum.2Shawn Clark to the author, email 23 January 2013. This was the first clue to what a Woodruff carriage actually looked like.

Another website visitor, Mark Thomas, suggested that the mysterious shadows that showed under the ammunition boxes were footboards.3Mark Thomas to the author, email 27 April 2015. We now had a fair idea of what a Woodruff carriage looked like, although details and dimensions were not easily extracted from the photo.

Detail of 1864 Woodruff photo showing the footboards beneath the ammunition boxes on the axles. Click the image to view enlarged version.

In 2016, my reenacting unit held its Spring Drill at Pilot Knob, and we had two visitors, a father and his adult son, Charles and John Berry. These turned out to be the owners of the Woodruff tube that had been on loan to the Sweeny Museum! And not only did they have the original tube, they claimed to have what remained of an original Woodruff carriage, the same one that Dr. Margreiter had gone to see in the 1990s.

Soon they sent me a photograph of the carriage, which could only be described as a metal skeleton, since hardly any wood remained except parts of the cheeks and about a third of the trail. The startling element was the metal frame that clearly supported the footboards, a feature that would have made no sense without the 1864 photo for guidance. Other details also matched the photo, so these were indeed the remains of an original Woodruff carriage.

The “skeleton” of the Berrys’ original Woodruff carriage, shown from the front, with the metal frame supporting the footboards indicated.

Photo by Charles and John Berry.

I determined to study the carriage remains and have a more correct replica carriage built for my Woodruff replica tube based on the remnants and the 1864 photo. But this did not happen as quickly as I hoped.

Although I communicated periodically with the Berrys, it was not until September of 2018 that I was able to visit them, study the carriage, and take measurements. A unique feature of the Woodruff carriage was the metal spine that ran from the axle down the underside of the trail to the end, where the metal was folded over to form the lunette and then run partway back up the top side of trail. Another metal bar ran on the top side of the trail from the axle to the floorboard support crossbar. While there was little wood remaining, all the bolts between the bars and in the cheeks were still in place, providing measurements for many of the dimensions.

The “skeleton” of the Berrys’ original Woodruff carriage, shown from the side.

The colored blocks are styrofoam spacers used to support parts in their original positions.

The metal spine folds over to form the lunette at the right.

Author’s photo.

To get a better idea of what the carriage actually looked like, I sent the measurements to my son who works as a mechanical engineer. He produced a CAD rendering based on the limited information I had collected thus far.

CAD rendering based on first set of carriage measurements. The rear footboard cross support is inverted from its position on the original based on a misreading of the footboard position on the 1864 photograph.

CAD rendering by Christopher Baehr.

An overlay of the CAD image onto the 1864 photo matched up fairly well, but revealed the first discrepancy in the evidence: The trail of the gun on the raft appeared much shorter than the physical remains showed.

In September of 2019, I was contacted by Terry Barnard, a resident of White Hall, Illinois, inquiring about plans for a Woodruff carriage. He and a local group were interested in replacing the existing carriage with a more correct one. We emailed on and off until I met him in White Hall in June 2021 so I could measure the original tube. He told me that he remembered playing on the gun when he was a child and told me that the old, apparently original carriage was replaced in about 1968. The only thing that seemed to remain from the original carriage was one trail handle, which matched that on the Berry’s skeletal remains.

He also provided a scan of a tiny old photograph, a detail from an old municipal postcard of the park where the gun was displayed. Although no real detail can be discerned, it does appear to show an original carriage. In August 2023, I found that John and Charles Berry had the original postcard in their collection.

White Hall postcard showing Woodruff on original carriage.

From the collection of John and Charles Berry.

In November 2019, I met again with the Berrys. John and Charles showed me the information they had on the provenance of their gun. Up until World War II, it had been displayed in a public park in Turney, Missouri, northeast of Kansas City. A local resident saved it from a scrap drive during the war and kept it. His widow later sold it to Charles Berry. Where it came from before it was in the park is still unknown, although it apparently was obtained through the efforts of a local Civil War veteran.4Personal collection of Charles Berry. [Click here for John Berry’s story of the provenance of his original.]

Photo of Berry Woodruff gun in a park in Turney, Mo., in 1940.

The original wheels have been replaced with wheels with Archibald hubs.

Charles Berry collection.

In February 2020, I contacted Steve Cameron of Trail Rock Ordnance in Tennessee about having a replica carriage built based on the skeletal remains and the 1864 photo. We agreed on a contract, and I proceeded to do as detailed an analysis of the available evidence as I could, to determine dimensions.

On 24 January 2022, I received an email from fellow reenactor Scott House in Cape Girardeau, Missouri. Scott was the lead in the successful effort to get that city’s Fort D, the last surviving earthwork fort of four that were built to protect the city during the Civil War, placed on the National Register of Historic Places.

In the course of his continuing research on the fort, he came across a circa 1937 newspaper photograph of the Depression-era building now on the site with some cannons in front of it. Scott asked me, “Can you identify either of the types of cannons in this photo?” The two by the building turned out to be French 75s from World War I, obtained by the American Legion post which met in the building at the time.5Scott House to the author, email 24 January 2022.

Photograph circa 1937 of cannons in front of the 1930s stone building at Fort D in Cape Girardeau, Mo. The two at the building are French 75s from World War I.

Photo by Garland D. Fronabarger used with the permission of the Southeast Missourian newspaper, Cape Girardeau, Mo.

Then I looked at the other gun. It was clearly a Woodruff on an original carriage! And its details matched the Berrys’ skeletal remains.

Then Scott sent me the other 1937 photograph, which showed the Woodruff from the front. This view provided valuable new details about the construction of the carriage. But there were still some details in these in these photos which were different from those from other sources.

The second circa 1937 Fort D photograph shows the Woodruff gun from the front.

Photo by Garland D. Fronabarger used with the permission of the Southeast Missourian newspaper, Cape Girardeau, Mo.

The wheels on the 1937 photo were 18-spoke dished wheels, while the 1864 photo showed 14-spoke wheels with dodge-style hubs, hubs with the spokes alternately offset in the hub instead of all in line. The footboards were in place, but they had apparently been sawn off in front of the axle. Estimates of the length of the trail in the 1937 photo again suggested a shorter trail length than the skeletal remains indicated.

The trail length issue was the most difficult discrepancy to reconcile. The 1937 and 1864 photos both suggested a trail length of about 84 inches from axle to the end of the lunette. The positions of the concrete blocks supporting the Woodruff in White Hall suggested the same. But the physical remains measured 93 inches, and the iron trail bars showed no evidence of having been altered. How do you argue with the physical remains? I couldn’t.

Although Woodruff specified that his guns would be delivered with the usual artillery implements, none of the photos show any attachment points for sponge buckets or sponge/rammers. It is unclear how they were carried on the carriage.

The coronavirus pandemic delayed the start of construction of a replica carriage, but the delay allowed additional information such as the Fort D photographs to come to light before design began. In January 2022, I traveled to the Trail Rock Ordnance location in Blaine, TN, to meet with Steve Cameron, share the latest findings, and begin the design process.

Randy Baehr and Steve Cameron, making the first drawings of the trail in January 2022.

Photo by Pat Baehr

To document the Berry carriage remains, I arranged for the carriage and the original tube to be 3D scanned. The Berrys consented to bring the carriage and tube to St. Louis for the job. Brett Wissel of St. Louis Restoration did the scanning and processed the images into a form that could be reproduced.

While John Berry and I were waiting in Brett Wissel’s shop for the 3D scans to be completed, I showed him the photos his father Charles had sent to the Historical Society of Quincy and Adams County, which were posted to the Society’s website.6Photos of Charles Barry’s [sic, Berry] Cannon and Carriage, Historical Society of Quincy and Adams County, Ill., Internet, accessed 28 March 2022 and earlier, https://hsqac.pastperfectonline.com/photo/B7C50465-7C61-467C-8CF8-572939321821 These were apparently taken shortly after Charles had purchased the gun (ca. 1993), when the wood parts of the carriage were still largely intact. I had seen these before but this time inspected them more closely and discovered additional details of the carriage that were not apparent in other photographs.

One of Charles Berry’s photos of his original Woodruff carriage, showing the spacer blocks between the trail and the cheek plates. The single board mounted above the iron axle is also clear, showing the iron axle was not boxed as in standard carriage designs.

Photo by Charles Berry, courtesy of the Historical Society of Quincy and Adams County.

Following the 3D scanning operation in St. Louis, John Berry delivered the carriage remains to Trail Rock Ordnance to have the metal parts cleaned and new wooden parts fabricated to restore the carriage. At the same time, I delivered my replica tube so it could be fitted to the new replica carriage. Having the original in his shop made Steve Cameron’s work much easier, since he could have all the original parts to inspect and measure when making new replica parts.

With the carriage remains on his worktable, Steve Cameron plots out a pattern for the trail.

Author’s photo.

Steve Cameron and John Berry work out a pattern for the cheek plates in Steve’ workshop.

Author’s photo.

Having the Berry carriage remains enabled Steve Cameron to make new discoveries about the construction of the Woodruff carriage. The original carriage was on its third set of wheels. The original wheels had a short wooden hub as shown in the photographs, the Turney photo showed these had been replaced with wheels with Archibald metal hubs, and the current state had the remains of larger wagon wheel hubs. Steve was able to remove the wagon hub remains without damaging the axle, revealing the original axle ends underneath. These were canted, indicating the original wheels were dished. The linch pin holes were also still there, confirming that the wheels were retained with linch pins, not nuts.

After removing the replacement wagon wheel hubs from the original axle, Steve Cameron found the original axle intact. The photos show the cant of the spindle, indicating that dished wheels were used.

Photos by Steve Cameron.

In disassembling the Berry carriage remains, Steve Cameron found an inscription on the underside of two metal parts that read “Tyrone”. We wondered, who or what was Tyrone?

Jean Kay of the Historical Society of Quincy and Adams County, Illinois, quickly responded that “Tyrone” was apparently a type of iron, and provided an image of a local advertisement from the Quincy Daily Whig and Republican of 10 January 1860, specifically advertising “Sligo and Tyrone iron”. 7Advertisement for George Ant. Roberts, Quincy Daily Whig and Republican, 10 January 1860, www.quincylibrary.org, Community History Archive, Quincy Historical Newspaper Archive, Internet, accessed 12 Sept. 2022. https://quincypublicil.advantage-preservation.com/viewer/?t=41361&i=t&by=1860&bdd=1860&bm=1&bd=10&d=01101860-01101860&fn=quincy_daily_whig_and_republican_usa_illinois_quincy_18600110_english_4&df=1&dt=4. Brown nodular hematite was mined near Tyrone, County Omagh, in what is now Northern Ireland, in the 18th and 19th centuries. This ore was 81% iron peroxide or 57% iron after processing, which made it among the richest iron ores found in Europe.8Robert Kane, The Industrial Resources of Ireland, Dublin: Hodges and Smith, second edition, 1845: 119, Internet, accessed 11 January 2023 and earlier, https://celt.ucc.ie/published/E840001-001/text004.html

Advertisement for Tyrone iron in the Quincy Daily Whig and Republican of 10 January 1860. Some iron parts of the original carriage were stamped “TYRONE”.

Image from From www.quincylibrary.org, Community History Archive, Quincy Historical Newspaper Archive.

In September 2022, Brett Wissel of St. Louis Restoration delivered the final renderings from the 3D scans that he did on the Berrys’ carriage and tube. He also created 3D renderings of the conical shot and the round shot and sabot, so replicas could be 3D printed.

I ordered a scale model 3D print of the carriage scan from a company in St. Louis. They also produced prints of the solid shot.

Amid the 30 other projects on order from Trail Rock Ordnance, Steve Cameron and his crew labored to create a gun carriage from what was really a jumble of disparate pieces of information, making up the plans as they went along, doing everything they could to meet the deadline of 1 October 2022.

As work on the carriage progressed, Steve Cameron provided updates. Here the wood parts of the carriage are mostly assembled.

Photo by Steve Cameron.

The last detail to be resolved was the method by which the ammunition boxes were attached to the floorboards. Only the 1864 Helena photograph showed the ammunition boxes, and details were not easily discerned, as seen in the enlarged detail below left. We could make out a U-shaped strap hinged at the bottom to a plate underneath the floorboard edge and a crossbar that appeared to span the U to hold it in place. The box was clearly set back from the front edge of the floorboard. There were no photos of the carriage from the rear that would suggest how it might have been attached on the back side. We started with a few assumptions:

- The boxes were symmetrical (no rights and lefts), so the attaching method had to be the same in the front and the back.

- The design of the carriage indicated that the boxes were placed on the floorboards from the front of the gun, given that the front U-strap was hinged and that it would be impractical to lift the boxes over the wheels from the side or push them up the floorboards from the rear.

- The crossbar rotated to clear the strap when open and to span the strap when closed.

From these we deduced:

- The attaching method on the back side was also a U-shaped strap.

- The rear strap was fixed rather than hinged, which provided a stop when sliding the box down the floorboard from the front into place.

To these, we added two additional practical considerations.

- Metal plates were added to the box outside the position of the U-strap that prevented the box from moving side-to-side. We thought we might have detected edges of such plates in the photograph.

- A wing nut, based on a design found on Revolutionary War carriages, was added to permit tightening of the crossbar against the U-strap, so carriage vibrations would not loosen the crossbar.

The final design may not be identical to what is seen in the 1864 photograph, but it is a reasonable interpretation based on the available evidence.

Left, enlarged detail of ammunition box in place. 1864 Helena photo.

Right, Replica ammunition box as constructed and installed. Author’s photo.

I picked up the completed replica carriage from Steve Cameron in Tennessee on 30 September 2022, in time to present it at the annual Company of Military Historians meeting a week later. Final assembly was not completed until the day I picked it up.

Steve Cameron and the author with the author’s completed Woodruff replica at delivery in the Trail Rock Ordnance shop September 30, 2022.

Photo by Pat Baehr.

The author with the Woodruff replica at the 2022 Company of Military Historians annual meeting in Moline, IL, Oct. 2022.

Photo by Pat Baehr.

The completion of a reasonably authentic replica Woodruff carriage, based on information largely acquired only in the last several years, was a milestone in my journey of discovery. But it was only a waypoint in the continuing quest for the hidden history of the Woodruff gun. Many findings, such as the Fort Madison and White Hall originals, had been in plain sight for decades but not identified. Some pieces of the puzzle had been known for some time by a few individuals but not widely disseminated. For instance, the Cape Girardeau photo was displayed on a historical marker there for several years (in a size so small as to obscure the details) before it was brought to my attention in its original form. Other pieces turned out to fit in a different place in the puzzle than originally thought.

The completed Woodruff replica. No photos of originals show this view. The rear retainers for the ammunition boxes are speculated, based on the assumption that the boxes were symmetrical. This view also suggests what the limber probably looked like, without the tube and cheek plates and with the trail configured as a limber pole for attaching two horses.

Author’s photo.

The completed Woodruff replica. Compare to the similar view in 1937 Cape Girardeau photograph.

Author’s photo.

The completed Woodruff replica with the ammunition boxes removed, balanced on the axle. This view shows the iron spine along the underside of the trail and the support frame for the footboards.

Author’s photo.

In the mid-1990s, the first cannon I researched was the Filley gun that I mentioned earlier. I had a copy of the handwritten note Giles Filley sent in 1898 to the Missouri Historical Society in St. Louis with his donation of what was presumably the last surviving example of the guns he had made. I wanted to find out where his guns might have been used and who used them.

The author’s Filley replica speculatively mounted on a Second Model Prairie Carriage.

Author’s photo.

The OR reported an January 1863 engagement in Bloomfield, MO, in which the 68th Enrolled Missouri Militia (EMM), a Union home guard unit, attacked a band of Confederate guerrillas with the help of two small guns “provided at private expense”. [Source] I thought perhaps these might be Filleys.

I found the ordnance receipts of the 68th EMM shortly after the unit was formed and discovered that they reported “round balls”, “mortar powder”, and “friction primers”, all artillery supplies, as being issued, but no guns [Source]. Since the guns were privately purchased, the fact that they were not reported as issued was not surprising.

The Battle of Pilot Knob State Historic Site had in its collection a history of the 68th EMM written in 2001 by Jack Mayes, a park volunteer and local historian, which said that the colonel of the 68th, James Lindsay, purchased three Woodruff guns for his regiment.9Jack Mayes, “The 68th Enrolled Missouri Militia”, https://mostateparks.com/sites/mostateparks/files/FD%20Related1.pdf; Internet. This information was disappointing but not implausible, since Lindsay was from Ironton, Missouri, and Woodruff guns were known to have been at Fort Davidson in Pilot Knob, right next to Ironton. Mayes posited that the Woodruff guns that were at Fort Davidson during the Battle of Pilot Knob were Lindsay’s, since the EMM as an organization was disbanded in mid-1863. On the basis of this account, for many, many years I asserted that more than 36 Woodruff guns were produced, because Lindsay’s purchases could not have come from those already accounted for. I did have some reservations about the Woodruff information in the article on the 68th. Mayes referred to a letter of reminiscence from H. C. Wilkinson, a member of the 68th, saying that its soldiers had molded their own lead conical shot for their Woodruffs.10H. C. Wilkinson to Cyrus Peterson, Letter No. 9 undated, Cyrus A. Peterson Battle of Pilot Knob Research Collection, Missouri Historical Society Archives, St. Louis. This was inconsistent, not only with everything I thought I knew about Woodruff guns at the time, but also with the reports in the OR about how the Woodruff ammunition boxes had to be rebuilt to accommodate the new cartridges. If these had been Lindsay’s Woodruffs, and they had always used conical rounds, why didn’t the new rounds fit in the boxes? I basically dismissed the reminiscence as misremembering 30 years after the fact. In early June 2022, John Berry sent me a transcription of James Lindsay’s 1898 newspaper obituary. It turned my Woodruff world upside down.

The obituary stated that Lindsay had purchased three guns from Giles Filley![Source] Suddenly, a number of inconsistencies in the Woodruff story simply disappeared. The 68th did mold their own conical rounds, because that’s what Filley projectiles were. The Woodruff ammunition boxes at Fort Davidson had never previously held conical rounds, so they indeed didn’t fit in the boxes when the new cartridges were received. Lindsay was a prominent Unionist Republican in Ironton, at the end of a rail line to St. Louis, so he very likely knew, or knew of, Giles Filley, a prominent Unionist Republican in St. Louis. Lindsay would have been unlikely to have known, or even heard of, James Woodruff or his guns. In reviewing the reminiscence letters, I found that Wilkinson never identified the 68th’s guns by name. But, the mystery continues: Wilkinson said he last saw “these pretty little guns” at Fort Davidson right before the fort was evacuated after the Battle of Pilot Knob.11H. C. Wilkinson to Cyrus Peterson, Letter No. 9 undated, Cyrus A. Peterson Battle of Pilot Knob Research Collection, Missouri Historical Society Archives, St. Louis. What happened to them? As guns of the same caliber as Woodruffs, were they misidentified by the Confederates who captured them, even though they would not have looked much alike?

Former Curator of the West Point Museum Les Jensen once told me that he never trusts anyone who is a self-proclaimed expert on a subject. As a recovering self-proclaimed expert on the Woodruff gun, I can only say that what is presented in this article is what I have concluded from the information I have at the time of publication. I’m certain there is more information out there to be revealed and perhaps even more original Woodruff tubes that remain to be identified. [Click here for a recent lead that didn’t pan out.]

Latest Developments

Since I first prepared this article, Civil War Times printed a postwar photo of a 1910 Grand Army of the Republic parade, probably in New York City, in which the veterans are towing a small cannon which appeared to me to be a Woodruff tube.12Illustration for the article: Jonathan A. Noyalas, “Union Veterans in the Valley”, Civil War Times, 62, 1, Winter 2023, p. 43. Original from Library of Congress, www.loc.gov/2014688449/ in the prints and photographs database. Bain News Service, Publisher. G.A.R. Parade. 9/21/10 date created or published later by Bain. After the magazine provided the source of the photo, Jack Melton, editor of The Artilleryman Magazine, examined the enlarged original image and determined that it was not in fact a Woodruff.13Jack Melton to the author, email 21 January 2024. I agreed. The enlarged image shows a flare at the muzzle instead of the flat muzzle band characteristic of the Woodruff, and the tube also lacks the Woodruff’s flat band at the breech. Melton also believes the photo shows a polished bronze tube, while a Woodruff would have been painted iron.

Woodruff gun on postwar carriage in Grand Army of the Republic parade in 1910.

Bain News Service, Publisher. G.A.R. Parade, 9/21/10 date created or published later by Bain. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2014688449/.

However, this effort was not wasted. Very shortly after my letter about this photo to Civil War Times was published14Author’s letter to the editor, “Woodruff Gun”, Civil War Times, 62,3, Summer 2023, pp. 6-7. I cannot identify the photo illustration of the cannon that is printed alongside the 1910 photograph along with my letter, but it is not a Woodruff gun., I received an email from a reader who had seen it, asking, “Do you know of any way to tell the difference between a Woodruff gun and a Filley Cannon?”15Bruce Bowers to the author, email 18 May 2023. I replied with the basic dimensional differences between the tubes, and the inquirer responded with photos―photos of what at first appeared to be another Filley tube!

Bruce Bowers’s tube. Note the round rimbases, flattened round breech, and long, thin cascabel neck, which are not seen on surviving Woodruff originals. The sight mount is not original.

Photo by Bruce Bowers.

Certain features matched those of the Filley example but not the Woodruffs―the round rimbases, the long, thin cascabel neck, and the somewhat flattened round breech. The owner, Bruce Bowers of Crawfordsville, Indiana, related the story that the tube had been found in a drainage ditch in Cape Girardeau, Missouri, by a lineman repairing downed lines after a storm. Bruce’s brother acquired it when his neighbor the lineman moved. Bruce got it from his brother in the 1970s and fielded it on a generic carriage for many years in his Confederate reenactment battery.

But when Bruce sent me more photos and measurements, it became clear that this was another original Woodruff tube, despite the similarities to some features of the Filley and the lack of some features common to all other surviving Woodruff tubes, namely beveled square rimbases and the the hole in the end of the cascabel. The overall length and general shape of the tube indicate that this tube is a Woodruff and not a Filley. This makes it the eighth known surviving Woodruff tube.

So I wondered, could this be the Woodruff in the photos of Fort D in Cape Girardeau, since that city was the original source of the tube? I looked more closely at the second photo from Fort D which showed the gun from the front. It appears to me that the one visible rimbase does not show square edges like other Woodruffs. This is almost certainly the tube in those photographs.

At left: Closeup detail of the Woodruff gun in 1937 Fort D photo. No edges are perceptible on the visible rimbase, indicating that it was round, not square.

At right: 3D scan of Berry Woodruff tube oriented to match the view at left. The edge of the square rimbase is visible in this view, the bottom side showing a dark shadow.

Rendering by Brett Wissel.

In December 2023, Bruce Bowers sold this Woodruff tube to the Friends of Fort D in Cape Girardeau, MO, returning it to where it was once displayed

A Turner crew fires the author’s Woodruff gun during a demonstration at the Fort D living history in Cape Girardeau, MO, September 3, 2023. Photo courtesy of James Lu Photography.

https://www.jamesluphotography.com/My-Photography-Class/20230903Cape-Girardeau-Fort-D/n-QqbtG6

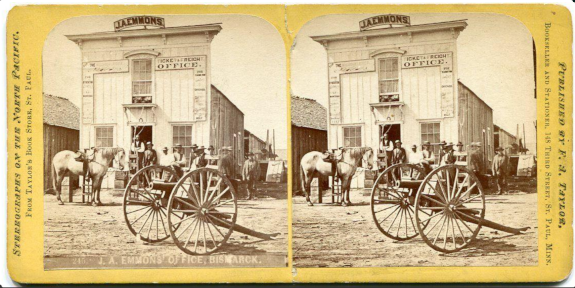

Just before Christmas 2023, I received a link from Paul Rosewitz, president of our local chapter of the Company of Military Historians and also a cannon owner. Paul had heard my presentation on the Woodruff gun at the Company meeting in Moline in October 2022 and had seen the new replica carriage. He had been looking at a Facebook page about clothing in the American West when he came upon a stereoscopic image from Bismarck, Dakota Territory, from the 1870s. In the middle of the street in front of a building was a cannon Paul immediately recognized as a Woodruff gun.

Stereoview photo of the J. A. Emmons Office in Bismarck, Dakota Territory, in the 1870s. Original online at https://www.worthpoint.com/worthopedia/bismarck-dakota-territory-emmons-1834876122?fbclid=IwAR3oTXZ7v8uDCwcUPQGBixuAP60tYGJo0H8Y0nA5dSW1anH1oH0KSoVkYxI_aem_AQpgh4nocmh0ypcBYz08P6wZAhjWmnO_MzXYy-3GWpjGuLpBxs7fsr0WEPfPPRR_0CY.

This example is very much like the one in the 1937 Fort D photos. It has 18-spoke dished wheels and also shows an apparently wooden handle that is attached to the left side of trail near the end, presumably as an aid to lifting the trail. This feature does not appear in other photographs where the angle of the photo does not show the left side of the gun trail, but it is seen in one of the 1937 Fort D photos. The ammunition boxes are in place, but the retaining hardware is different, showing a single bar strap instead of the U-shaped strap on the 1864 Helena photo.

Impact of Recent Discoveries

The problem with doing research is that it never ends. But when the objective is to create something, you have to go with the information you have at some point or wait forever. The first carriage for the Woodruff replica in the museum of the Battle of Pilot Knob State Historic Site is an example. It was very wrong, but it was the best guess based on, in this case, the lack of evidence available at the time.

At the time that Steve Cameron and I were ready to begin design work on a new replica carriage, the only known photos of Woodruffs on original carriages were the 1864 Helena photo and the two 1937 Fort D photos. The first decision was which wheel design to use, the 14-spoke wheel of the 1864 photo or the 18-spoke wheel of the Fort D photos. While I felt that both were probably authentic, I chose the 14-spoke version because it was documented on a known period photo, and so was guaranteed authentic to the period, even if it might have been a field replacement of the original. A commenter on a message board asserted that the dodge-style hub with offset spokes was not in use during the Civil War period, but a photo of a Billinghurst-Requa battery gun also shows wheels with this style hub. (Click here for enlarged views of the dodge-style hubs and more information.)

A more difficult design choice was the size of the ammunition boxes. At decision time, only the 1864 photo showed the ammunition boxes at all, and inferring dimensions from this photo alone was challenging.

At least one dimension was relatively easy to approximate. The known size of the shot and the known distance from the cheeks to the wheels based on the carriage remnants fairly well fixed the width of the box as accommodating four shot across and a box width of 10½ inches, assuming ¾-inch lumber. The height appeared less than the width but still had to accommodate the estimated height of a fixed canister round, the size of which is still not well established. (Click here for a discussion of the mathematics attempting to derive the heights of Woodruff rounds.) The replica box height came out at 8 inches to the bottom of the lid, which I now think is a little short of what it should be, I can’t say at this time exactly by how much, but at least ¾ inch.

The foreshortening of the image in the 1864 photo made estimating the length of the box even more difficult. After examining the photo, I rather arbitrarily guessed that the box would hold 20 rounds in a 4×5 configuration, with the middle row of the box centered over the axle for balance. I figured this would produce a loaded box weight of around 60 pounds, a heavy lift for a box without any handles. This resulted in a replica box length of 13½ inches. Hardware for the box, not visible in the 1864 photo, was patterned on that for a First Model Prairie Carriage ammunition box, in the absence of any other information. The main differences were that handles and iron corner guards were omitted, as neither was visible in the 1864 photo.

The discovery of the Bismarck photo provided a second view of the ammunition boxes, one that gave a different angle. It suggests a longer box length than that produced for the replica, probably about 16 inches, for a 4×6 configuration, or 24 rounds per box. This would still comfortably fit on the footboards, although it would shift the box forward about an inch so the center would still be over the axle. This is consistent with the Bismarck photo which shows the front edge of the footboards protruding beyond the front edge of the cheeks, while the current replica has the footboards not quite reaching the front edge of the cheeks. The lack of contrast at that spot of the 1864 photo made that detail difficult to perceive.

This detail from the Bismarck photo shows the box length on the near side extending just past the second spoke to the rear of the vertical one, indicating a longer box than first estimated. Also, the footboard can be seen extending beyond the front edge of the cheek on the far side of the tube. The lack of contrast in the photo at the middle of the box near side does not reveal any information about a hasp for securing the box lid.

Compare the Bismarck photo to this similarly angled photo of the replica. The replica box does not extend as far to the rear.

Neither the 1864 nor Bismarck photo are sharp enough to show detail at the edge of the lid. Standard artillery ammunition boxes were covered in either copper sheeting or painted canvas, which would have had fasteners along the edges of the lid, but none are visible on either photo. With only the 1864 photo available to me at decision time, I opted for a copper covering, a decision strongly influenced by the fact that I already had a sheet of copper in hand to use for that purpose. It is entirely possible that Woodruff box lids were in fact not covered at all.

Future replica Woodruff carriages should incorporate these new discoveries.

Click here for the history of the Woodruff Gun.

Click here for author’s acknowledgements of many of the people who contributed to this article.

Much of the information on this page and in the companion page “The Woodruff Gun” was also published in the Winter 2023 issue of Military Collector & Historian, the quarterly journal of the Company of Military Historians and again in the Spring 2024 issue of The Artilleryman Magazine.

If you have additional information about the Woodruff gun, contact: